Report: SalaaMedia

A state of judicial vacuum has prevailed in Darfur region recently due to current conflict, as continued battles suspended judicial institutions when civilians needed justice badly. Accordingly, the region’s residents opted to relying on community courts run by tribal leaders. In some states of the region emergency courts were also established by the Civilian Administration System formed by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Community Courts:

Darfur region has historically been known for the existence of community courts run by tribal leaders to decide on cases within local communities. Community courts rely primarily on local laws and customs that govern rural communities. Tribal leader chairing such courts has been enjoying a variety set of powers and jurisdictions constituted by the Sudanese laws for a long time and most recently 2005 constitution. however, Sudan moved to enact laws to regulate and codify the work of the native administration.

Emergency courts

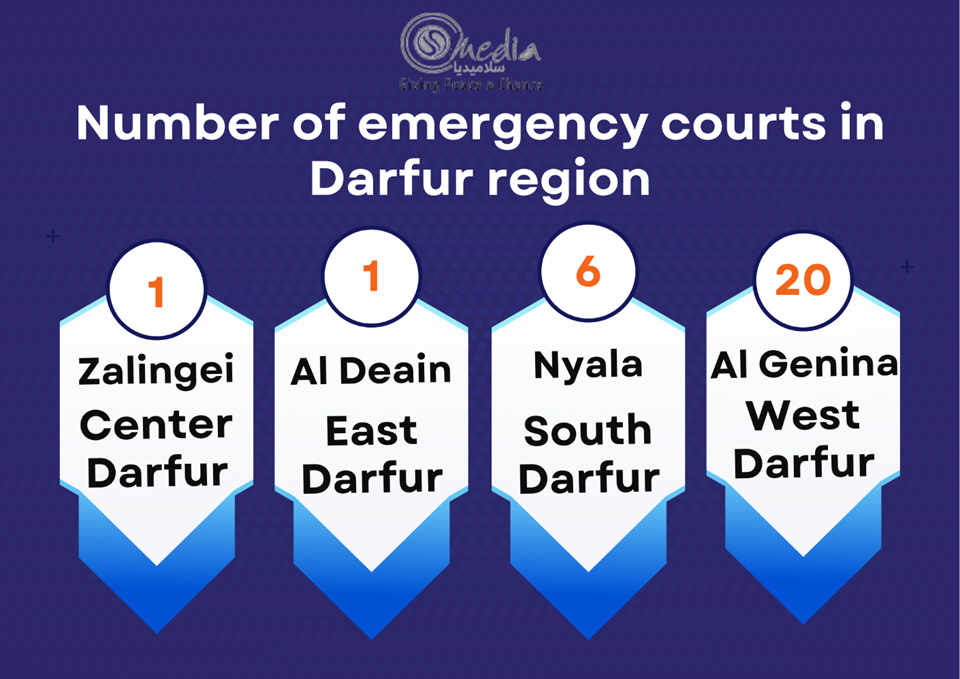

The judiciary system in Sudan consists of the police, prosecutors, and courts, disrupted in several parts of the country. But because of the war especially in Darfur region this apparatus stopped completely due to destruction of its premises. The war led to damage and loss of case files, in addition to the absence of judicial personnel, nevertheless, the judiciary resumed after RSF took control of four states in the region. These Civilian Administrations in Darfur issued decrees calling for the formation of emergency courts, in addition to activating police and public prosecution. In West Darfur state, the head of the state’s Civilian Administration, Al-Tijani Al-Taher Karshoum, established 20 emergency courts in various localities in the state. According to the decree, these courts consist of (chairman and members from the Native Administration). The head of the Civilian Administration in South Darfur, Mohamed Ahmed Zein, followed the same approach by deciding to establish six courts,

headed by former judges, prosecutors, native administrators, and some notables from Nyala town. In the same direction, in June 2024, East Darfur State held a workshop to legitimate forming a judicial authority in the state in the absence of the official state apparatus. Journalist Mohamed Saleh Al-Bishr said that, based on the workshop’s recommendations, the head of the Civil Administration of the state decided to form a judicial body headed by the lawyer Abdul Rahim Mohamed Tibin, and a public prosecution headed by Deputy Prosecutor Mahmoud Al-Muta’fi. Tibin, in turn, appointed 15 judges at various levels assistant judges. As for Central Darfur, the judiciary unit was formed headed by the Native Administration Leader, Chief/ Mahmoud Sowsal, and a public prosecution unit headed by the lawyer Abdel Raouf Mustafa.

Shaima Haren Al-Rumaila, Minister of Culture and Information and the spokesperson of the state’s Civilian Administration, said that the judiciary formed a court Zalingei town leaving the localities to operate community courts run by tribal leaders. Shaima explained to SalaaMedia that the court began its work to decide on minor cases, while major crimes such as murder are looked at through the common customary setting known (judiya) system.

Jurisdiction:

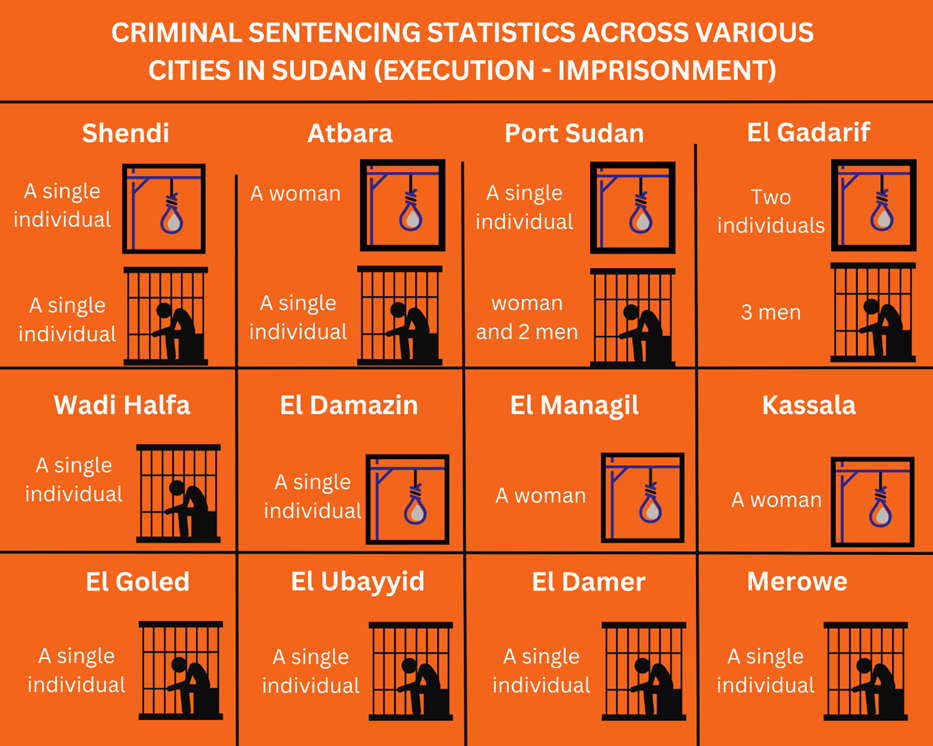

Article 6 of the annexed second additional protocol of Geneva Conventions, on the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts, requires adherence to a number of procedures to protect civilians who are subject to trial during internal conflicts. Dr. Wissam Al-Din Al-Okla, professor of international law and diplomacy at the Turkish Academic Institute of Science and Technology, believes that international law authorizes the de facto authority to establish judicial courts, with the aim of prosecuting people who commit crimes in order to control security in areas under its control. The courts must apply the laws in force before the conflict, and if they want to change the laws, they must choose a lighter law. Based on what SalaaMedia team recorded, the courts established in Darfur states relied on pre-war Sudanese laws to look into some cases, while some courts applied emergency laws on other cases, with imposing financial fines. Accordingly, a community court in Nyala town sentenced a civilian to imprisonment pending to payment and held him to pay an additional amount as fees to the police and the court, based on a report against him by Mr. Idris Saleh at Nyala Central District, regarding a commercial transaction among both of them. In another case, in accordance with the Personal Status Laws on spouse upkeep; Qadra Court in Nyala issued a prison sentence against a civilian pending to payment. Meanwhile, 37 people sentenced to jailed and fined for violating emergency orders of the Civilian Administration in South Darfur. The Civilian Administration in the states gave policemen who returned to work the powers to arrest, detain, with the help of legal advisors, in addition to implement rulings of community courts. On the other side, emergency courts were established in a number of states under SAF control. According to the emergency laws, these courts issued penalties against a number of civilians arrested on charges related to cooperation with RSF. Based on the trials which took place in Atbara, Gedaref, Karari, Kassala and Port Sudan, sentences ranged from death to lifetime imprisonment.

Legal and Constitutional Basis:

The Lawyer Al-Agib Al-Zein Jabakallah told SalaaMedia that according to International Humanitarian Laws and Human Rights Laws, courts, whether in conflict areas or elsewhere, must be subject to the conditions of a fair trial. He added, “In all cases, the trial must be fair, and in order for it to be fair, it must meet specific conditions“. He pointed out that, the conditions are not limited to bailing guarantees, interrogations, investigations, referral to court, as well as legislative guarantees. The defendant must face trial by natural laws but not subjected to any arbitrary procedures, or any procedures that undermine his/her rights to a fair trial. He added that civilians must not face trials before military courts, and institutional guarantees should be in place to ensure the basic conditions for fair trial at the primary court, court of appeal, supreme court, and the constitutional court. He stressed that if these conditions are not met, the trial becomes unfair and represents a violation of International Humanitarian Laws.

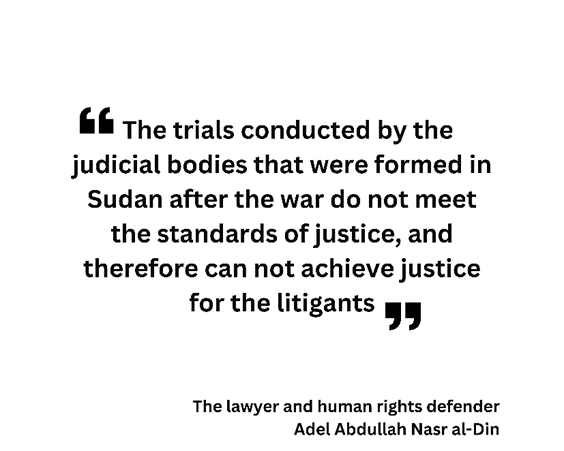

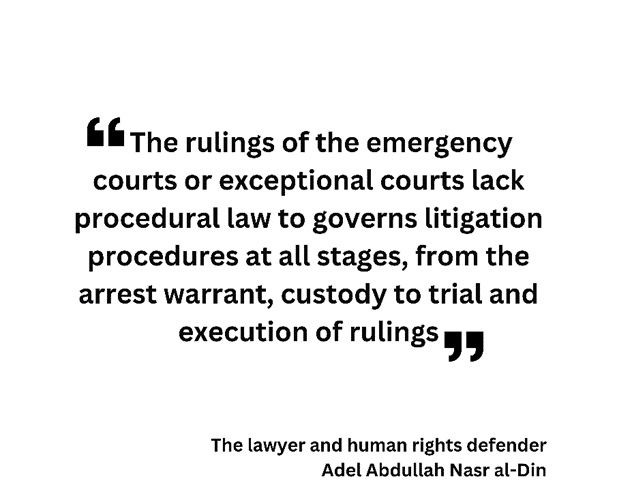

The lawyer and human rights defender Adel Abdullah Nasr al-Din stated that “the trials conducted by the judicial bodies that were formed in Sudan after the war do not meet the standards of justice and therefore cannot achieve justice for the litigants”. Nasr al-Din told SalaaMedia that these courts operate according to a mixture of laws (the state’s law before the war and the emergency laws), in addition to the fact that the emergency laws in force at some courts were not legislated by a legislative body, besides that the judges appointed by the Civilian Administrations in Darfur whether they are lawyers, prosecutors, or tribal leaders, are not qualified. Adel explained, “The jurisdiction of community courts does not exceed minor trials which are not presided by a third-ranking judge, and their rulings do not exceed misdemeanor cases.” He stated, “The rulings of the emergency courts or exceptional courts lack procedural law to governs litigation procedures at all stages, from the arrest warrant, custody to trial and execution of rulings“. Pointing out that all of these factors give litigants the right to file a constitutional appeal against the government of Sudan when the war ends. He added, “In the event of exhausting all litigation stages within Sudan, the applicant has the right to resort to alternative judiciary regionally or internationally.”

Darfur region has been under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) since 2005, when the UN Security Council issued the resolution 1593, referring the file of violations in Darfur to the ICC. Based on the resolution, in 2008 arrest warrants were issued against a number of leaders of the Salvation (Ingaz) regime, led by Omar al-Bashir. In 2021, one of the defendants, Ali Abdul Rahman, known as Kushayb, surrendered to the ICC where trial sessions are still ongoing.

Fact-Finding Mission (FFM)

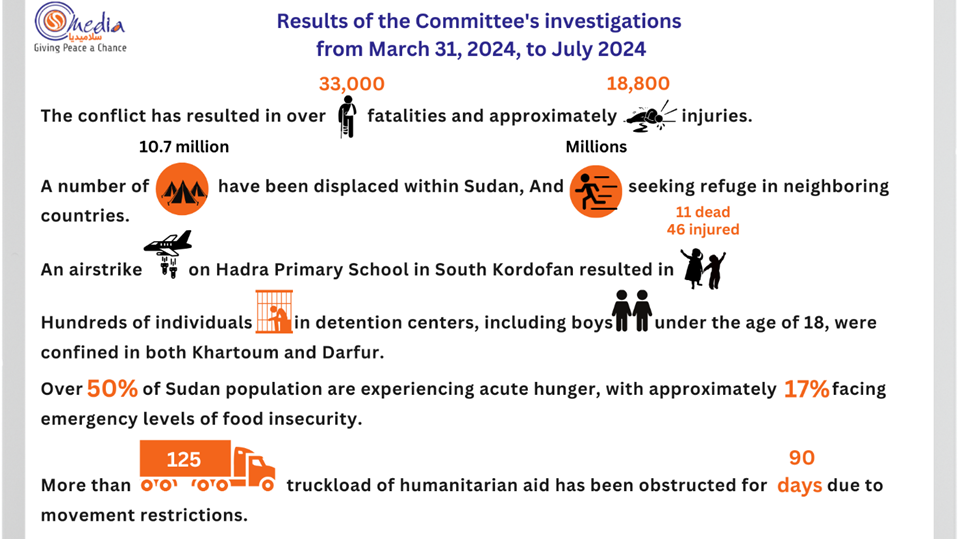

On 11th October 2023, the Human Rights Council decided to establish an independent international fact-finding mission for Sudan to investigate and substantiate all alleged violations and abuses of human rights; violations of international humanitarian law and to establish the facts; circumstances and root causes, as well as the crime related to the context of the ongoing armed conflict since April 15th, 2023. It also aims to collect, consolidate and analyze evidence of violations and abuses; and systematically record and preserve all information, documents and evidence, in consistency with the international best practices, for possible future legal action. Where possible, the Mission should seek to identify individuals and entities responsible for violations or other relevant crimes. However, the Mission issued a report report last September 2024, after six months of investigation. The report pointed out that, the warring parties in Sudan have committed a horrific range of human rights violations and international crimes, which many may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. The report found that the SAF, RSF, and their allied forces were responsible for widespread patterns of violations. The report stated that the definitions used in the Sudanese legislation are narrower than the scope considered by the international law, such hinders the accountability at the national level for the full scope of international crimes committed. The Mission noted that it was unable to obtain information RSF Civilian Administrations’ established courts and their activities, stating, that it appears to have had no clear impact on the violations committed by RSF and its allied militias. The Mission expressed concerns over courts being established outside the law framework, consequently lacking legal basis and the necessary assurance for fair trial. Nevertheless, in October 2024, the Human Rights Council extended the Mission’s mandate for an additional year, despite objections by Sudan government.

Regarding convicted people during the conflict, whether they have the right to testify before the FFM or international courts, the lawyer Al-Aqib Jabakallah believes that “nothing prevents the Fact-Finding Committee from asking them about the trials that they have been subjected to, perhaps it is systematic process targeting certain categories or groups to violate their rights, including the right to life or confiscation of property. In this context the trial in Sudan seems like a sword to silence or eliminate some groups or individuals”. He explained that testifying before anyone has nothing to do with convicting any person of a crime, but rather related to the content of his/ her testimony. If a person was present or witnessed the events, or had knowledge through a third party, then the information he obtains, if provided or revealed, could prove or refute the responsibility of a person, group, class, or institution for a particular violation. He added, “Conviction of a criminal offense doesn’t prevent testimonies that can be used to prove guilt or innocence. Therefore, those who were subjected to trials during this war can’t be deprived later from the right to testify before international mechanisms.”

By examining the judicial systems that emerged during the current war in areas under the control of both warring parties, that most emergency courts within SAF controlled areas, adopted the Sudanese Criminal Laws and the Emergency Law, to file charges under Articles (51/A, 65 – provoking war against the state and aiding terrorism), which amounts to death or life imprisonment penalties. On the other hand, the courts in RSF controlled areas mostly resorted to the Sudanese Civil Laws, in addition to the Emergency and Negative Events Law, which penalties does not exceed financial fines or imprisonment for months. Therefore, lack justice standards are common denominator in courts of both parties, where there is no integrity in interrogation or investigations, and defendants are deprived of the right to defense or appeal. Therefore, national and international organizations must play an oversight role by putting pressure on parties to the conflict to respect human rights and guarantee justice, in addition to continue monitoring and documenting violations committed by both parties to ensure zero impunity.